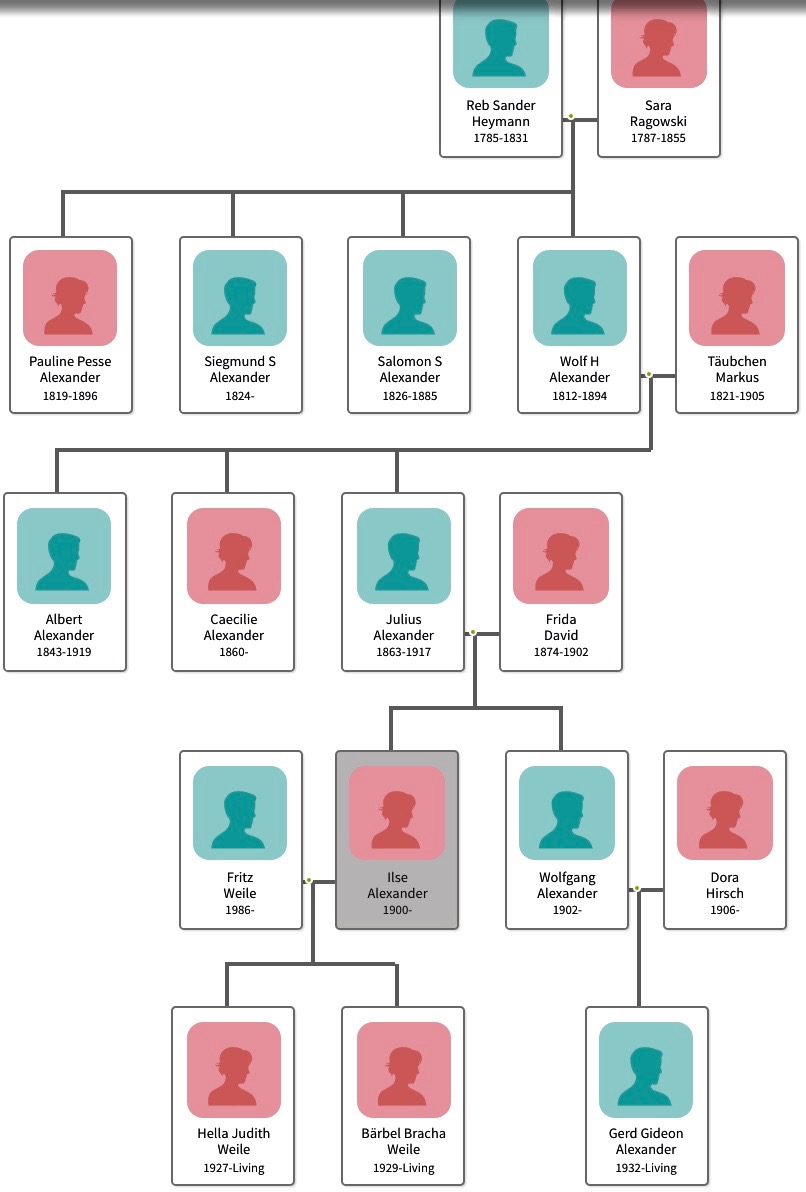

Siegmund and Salomon Alexander did not come penniless since they intended to open a business in New York. One might hope that they had been warned about the so-called “runners” or agents of boarding houses near the waterfront, whose principal income was extorted from newly arriving foreigners just like the two brothers. Perhaps they had been given an address of a boarding house on the lower East Side where they eventually would open their store.

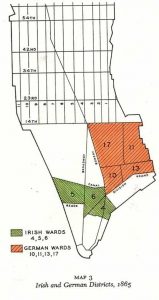

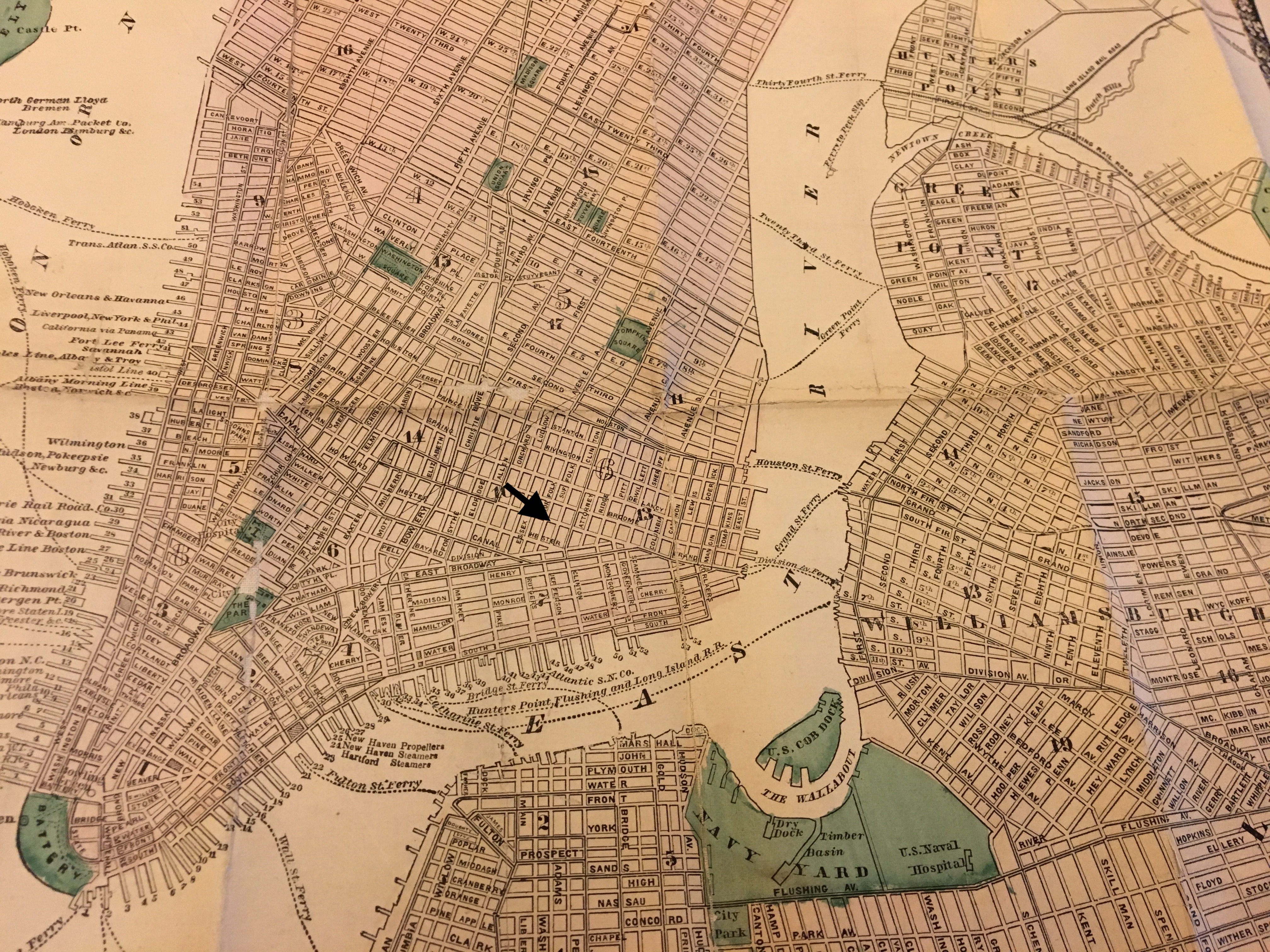

At that time, it was called Kleindeutschland, Little Germany for the vast number of German immigrants who had come to settle here as early as 1847. It was bounded by the Bowery to the west, Division Street and the east end of Grand Street to the south, and the East River to the east. The northern boundary varied as the enclave grew. Although immigrants from other countries lived here, especially those from Ireland, the German language and culture were dominant.

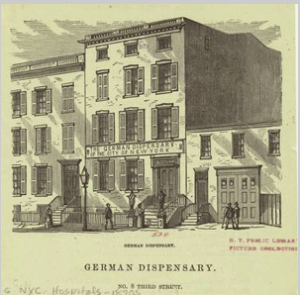

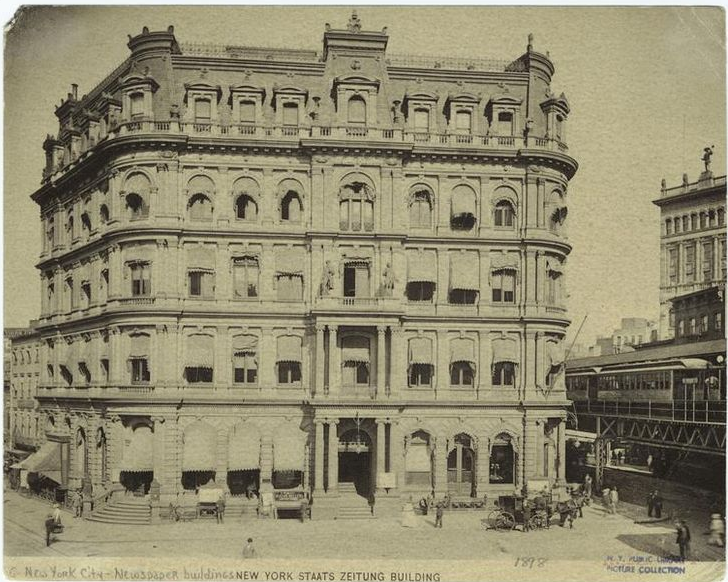

By 1855, Manhattan was considered the third largest “German” city in the world, after Berlin and Vienna. And by the 1870s, roughly 30% of New York City’s population was made up of German immigrants and their American-born offspring. Most of them lived in Kleindeutschland, then the German cultural capital of the United States.[16] One could easily live here without speaking English as all the usual financial and business-related  institutions were geared specifically to the German culture and language. The German Dispensary brought medical services to the population, while the Free Library and Reading Room, Freie Bibliothek und Lesesaal, still standing on Second Avenue, became a mainstay of the neighborhood. There were also numerous banks and insurance companies, as well as newspapers that not only informed the citizenry of current events, but also reflected various political and social points of view. The most famous was the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung, whose long history continues even today, if in a much smaller and politically less significant way.”[17]

institutions were geared specifically to the German culture and language. The German Dispensary brought medical services to the population, while the Free Library and Reading Room, Freie Bibliothek und Lesesaal, still standing on Second Avenue, became a mainstay of the neighborhood. There were also numerous banks and insurance companies, as well as newspapers that not only informed the citizenry of current events, but also reflected various political and social points of view. The most famous was the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung, whose long history continues even today, if in a much smaller and politically less significant way.”[17]

It is here in Kleindeutschland that I hope to find more information about the Alexander brothers. I start by looking through the New York City Directories, which luckily are all digitized and online starting as early as 1786.

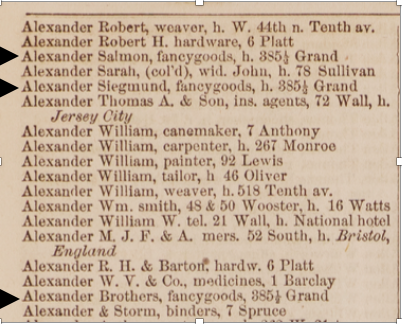

In the 1853 edition, I find the first entry and proof that Siegmund and Salomon truly lived in Kleindeutschland.

The brothers are listed three times, each one individually, and with their store, which they called Alexander Brothers. Unfortunately, the first „o“ in Salomon is missing and my great-great-great-uncle has become a salmon. Sarah Alexander, who is listed between them, is not a relative.

The directory gives a person’s profession and address. So, I learn that Siegmund and Salomon are merchants of Fancy Goods. The letter “h“ stands for “home.“ Their apartment and their store are in the same building on 385½ Grand Street.

William Perris’ street atlas lists the Alexander property in the 10th and 13th wards. The property is in red, which indicates that it was a stone or brick building. The dotted line between 385 and 387 tells me that the building 385½ was connected to the buildings on its left and its right. It might have been an extension. Unfortunately the number of floors is not provided, but since it is a dotted line, the house is at least two stories high, since the key stipulates there is a store on the ground floor. The store would have been in the front so that patrons could enter from the street.[18] The living quarters would have been behind the store or above it. If they were lucky, they may have had a small washbasin in the apartment, but no running water. They would have had to carry water from a dispensary in the street or from the backyard, where the toilets were located and women did the laundry.[19] Houses back then also had no electric lights. Light usually only came in through the small windows during the days, and at night one used candles.

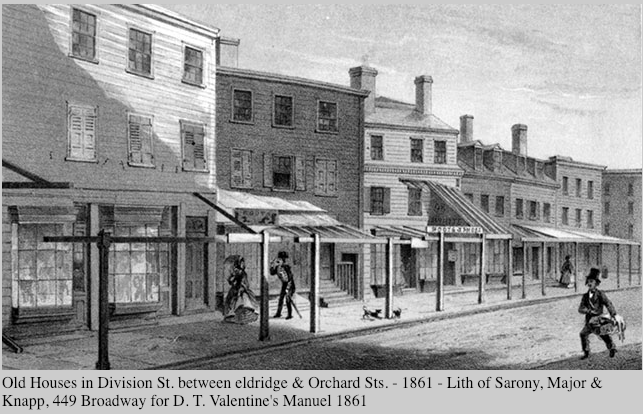

Grand Street in 1853 most likely looked similar to Division street, which lay a little below Grand Street.

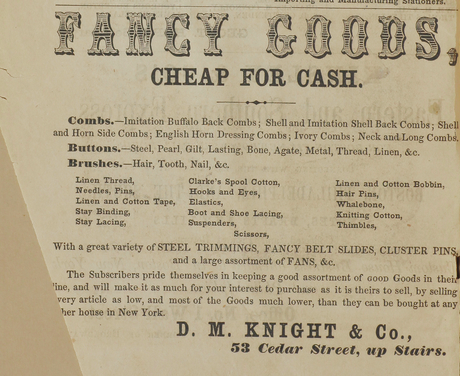

I am sure that where my ancestors first lived was not a very luxurious place but it was their own, and it seems that they did not have to share it with anyone else. In addition, they had their own store for Fancy Goods. But what exactly were “Fancy Goods?” In the online directory from 1854, I find an advertisement from D.M. Knight & Co. They sell combs, buttons, and all sorts of brushes, suspenders, scissors, linens, threads, and much more. Of course, at D.M. Knight & Co., everything is cheaper if one pays in cash.

Jan Whittaker, the author of The World of Department Stores, told me that fancy goods stores more or less predate the rise of department stores, and she stated they encompass quite a few items, including “notions” and perhaps fabrics that would have been used for women’s fancier clothes whereas “dry goods,” a term that the Alexander brothers listed next to their store in 1859, implied more basic, everyday fabrics, but also clothing.

In this 1854 New York City directory, my uncle was still listed as Salmon [sic!], but I can see from the entry that they must have bought the building next to it, as the store’s address had changed from 385½ to 387 Grand Street. It was located between Suffolk and Norfolk Street.

Only a few steps from their house was Essex Market, back then a three-story, elongated brick building that looked a little like a fortress from the Middle Ages with massive, square-shaped towers at each corner. On the ground floor were twenty different vegetable and poultry stands, eight butter and cheese stalls, six fish stalls, twenty-four meat booths and two stalls for smoked meat, two more for coffee and cakes, and one booth for tribe. On the first floor was a police station, a prison, a court and a dispensary. At the other end of the street, toward the East River, was the Grand Street ferry pier. It was one of the many ferries that brought people from the Lower East Side to Brooklyn and back. Walt Whitman beautifully described the daily ferry crossings beautifully on the East River in his poem Crossing Brooklyn Ferry. Also, my great-great-grandfather Albert, Salomon‘s and Siegmund‘s nephew, would soon take this ferry to cross the East River to look for a suitable place to live and work.

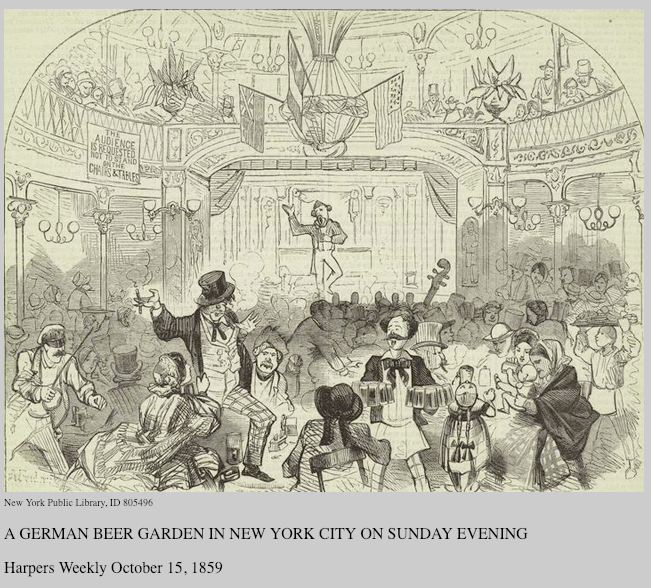

Kleindeutschland comprised roughly 400 blocks, with Tompkins Square Park at the center. Avenue B was called German Broadway and was the main commercial artery of the neighborhood. Every building along the avenue followed a similar pattern–workshop in the basement, retail store on the first floor, and markets along the partly roofed sidewalk. Thousands of beer halls, oyster saloons, and grocery stores lined Avenue A, and the Bowery, the western terminus of Little Germany, was filled with theaters. And you could find a myriad of organizations and fraternal societies oriented towards a wide variety of interests and goals. I cannot say if the two brothers joined any of these, but I am sure they went to music and theatre performances, as singing and performing has always played an important part in our family. For every occasion, be it a birthday, a wedding, or anniversary, a play, poems and/or songs were written and performed. One of the many examples that I found in my Aunt Judith’s treasure trove, when I visited her in Israel in January 2019, was a play by Albert’s youngest son Julius Alexander that he had written for his parents’ Silver Wedding celebration. (Albert was Siegmund’s and Salomon’s nephew, who would come to work for them in New York in 1857.)

The Alexander family always found reasons to celebrate, we love music, and theater, enjoy singing, good food and drink. Undoubtedly, Siegmund and Salomon would have frequented the many beer halls and beer gardens in Kleindeutschland, where they not only served German beer and good food but commonly also presented a variety of shows and music with dancing and were quite appropriate for family gatherings and socializing.[20]

Might it be—I wonder—that it was in one of these beer halls that Siegmund made the acquaintance of Fanny Liebmann? Fanny, ten years younger than he, had come with her family to America from Bopfingen, a small town in Baden-Württemberg. On the „Manchester’s“ passenger list of 1854, I find a Fanny who sailed with her parents and her two sisters from Liverpool to Philadelphia. The name and age fit and it could be “my“ Fanny, but how did she come to New York? On the New York census list from 1855, I find a Fannie Liebmann, daughter of Samuel and Lara Liebmann from Germany. Her father is a “Braumeister“ and owned a brewery in Brooklyn. I do not know which of the two Fanny’s is the one Siegmund met, maybe it is neither. Still, I imagine that Siegmund met his Fanny in a Beer Garden in Kleindeutschland. I see her as a jolly young woman, who had a good sense of humor and an infectious laugh. Siegmund would have liked her instantly. I imagine her coming to his store on Grand street to buy a comb, or needles or a few yards of velvet for a new dress. They talk in German and learn that they both love music and theater. They might have visited one of the many Minstrel shows in the Bowery Theatre or listened to Lortzings Zar und Zimmermann und Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer‘s Der Glöckner von Notre Dame.[21]They both would have loved the fun and industrious Bowery of which Whalt Whitman wrote many years later: “The most heterogeneous mélange of any street in the city; stores of all kinds and people of all kinds are to be met with every forty rods…You may be the President or a Major-General, or be Governor, or be Mayor, and you will be jostled and crowded off the sidewalk all the same.”[22]

By 1856, Siegmund and his brother were successful merchants, their store made a good profit, and in Fanny, Siegmund found the woman he wanted to share his life with. One evening in summer of 1856, he asked her to marry him and she happily accepted. They were married a year later.

By 1856, Siegmund and his brother were successful merchants, their store made a good profit, and in Fanny, Siegmund found the woman he wanted to share his life with. One evening in summer of 1856, he asked her to marry him and she happily accepted. They were married a year later.

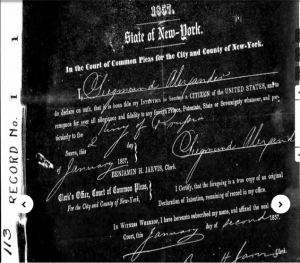

1857 was a year with many changes for the Alexander brothers. They changed their store’s name from Fancy Goods to Thread & C., in order to emphasize yarns, fabrics, and anything to do with clothes making. Siegmund applied for US citizenship which was granted three years later on October 11, 1860, and two more family members from Prussia arrived just in time for the wedding. Siegmund’s brother Wolf’s son Albert Alexander and his sister Pauline’s son Alexander Gumpert were ready to learn the trade and worked as apprentices in their uncles’ store, adding to the ever growing population of New York.[23]

Next: Chapter VI Albert and Alex Alexander: Relatives arrive in New York.